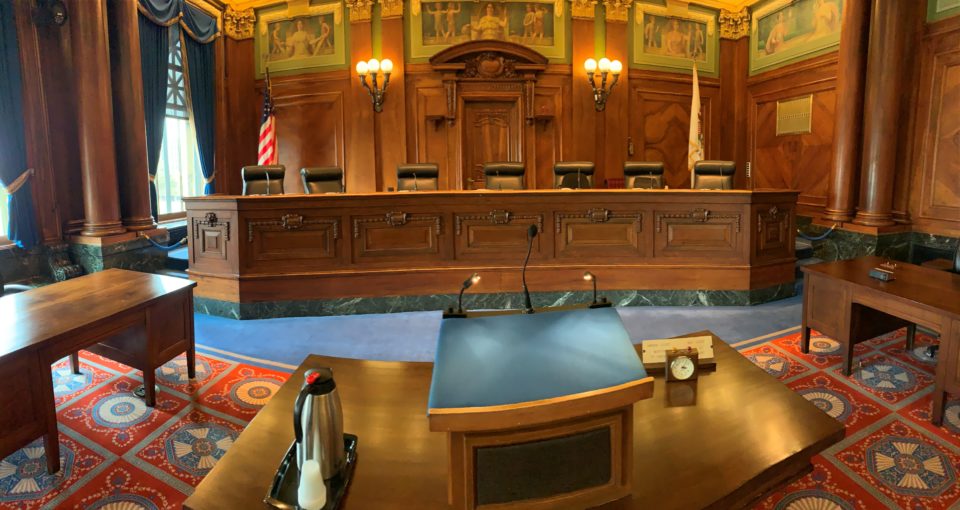

On March 13, 2019, Kevin Green of Goldenberg Heller argued before the Illinois Supreme Court in Nichols v. Fahrenkamp, Case No. 123990.

This case presents the issue of whether a guardian ad litem acting within the scope of his appointment in a probate proceeding is an agent of the Court and, therefore, entitled to quasi-judicial immunity from claims of negligence.

This is a matter of first impression for the high court, and the Court’s ruling is expected to provide much-needed clarity about the duties and immunities for individuals appointed as guardians ad litem in probate proceedings.

A video of the argument can be viewed here.

Background

The underlying case involved the personal injury settlement fund created for plaintiff when she was a minor. The plaintiff’s mother was appointed as the guardian of her person and her estate, and the court was required to approve any disbursements of the settlement fund until the plaintiff turned 18. The court also appointed a guardian ad litem. Over the next few years, the mother made requests for disbursements to pay for expenses related to the minor, the guardian ad litem recommended approval of several of these requests, and the probate court approved the disbursements.

After she turned 18, the plaintiff claimed that her mother dissipated the settlement funds, essentially by lying in the disbursement requests about what the money would be used for or how much was needed. The plaintiff sued her mother, but did not recover everything she thought she should, largely because the court would not reexamine or go behind the probate court orders approving each disbursement. Plaintiff did not appeal the decision. She did, however, then sue the guardian ad litem for negligence.

The Trial Court Grants Summary Judgment

The guardian ad litem moved for summary judgment, arguing he was subject to quasi-judicial immunity as an agent of the court. Although this was a matter of first impression for the court, the appellate courts for the First and Second District have each held that a “child representative” in divorce or custody proceedings (who performs more functions than a guardian ad litem in such proceedings) is entitled to quasi-judicial immunity. The trial court followed these and other decisions to find that the immunity applied. The plaintiff appealed the decision.

The Appellate Court Reverses the Trial Court

On appeal, a divided panel of the Fifth District reversed, finding guardians ad litem may have immunity in divorce or custody proceedings, but not in probate proceedings. See Nichols v. Fahrenkamp, 2018 IL App (5th) 160316.

The Appellate Court held that the guardian ad litem “owed a duty to plaintiff to render advice and to protect plaintiff’s assets and interests arising out of the underlying personal injury settlement.” Id. ¶ 14. This meant that the guardian ad litem “had a duty to act as an advocate on behalf of plaintiff.” Id. In light of this duty, summary judgment was inappropriate because a question of fact remained as to whether the guardian ad litem “fulfill[ed] his role as plaintiff’s advisor, advocate, negotiator, or evaluator.” Id.

Thus, the Appellate Court held that the guardian ad litem had no immunity whatsoever because he “was not simply a neutral party *** [but] was a licensed attorney, an officer of the court, who should have understood the need to protect the assets of his ward,” and he had a duty “independent of merely acting as an arm of the court.” Id. ¶¶15, 17.

Finally, the Appellate Court acknowledged that guardians ad litem are afforded absolute immunity in dissolution of marriage and child custody proceedings. Id. ¶ 16. Relying on Vlastelica v. Brend, 2011 IL App (1st) 102587, ¶ 23, however, the Appellate Court explained that the only rationale for such immunity was to allow guardians ad litem to fulfill their obligations without worry of harassment or intimidation from dissatisfied parents—and this rationale did not apply in this case. Id.

The Appellate Court Dissent

The Appellate Court included a dissent by Justice Goldenhersh, who argued that the majority’s determination that the guardian ad litem was not entitled to qualified or absolute immunity “runs contrary both to sound authority and is impractical in practice in our trial courts.” Id. ¶ 23. Further, the dissent explained that the majority’s decision would have consequences “adverse to the effective administration of justice in such an important area,” such as:

-

requiring trial judges “to provide specificity in directions to the guardian ad litem, which may or may not be effective, may or may not cover the factual situation at issue, and may very likely be premature in the development of the litigation in which the guardian ad litem is acting, since the guardian ad litem’s appointment would likely be early in the litigation and prior to development of facts and issues”; and

-

imposing upon the guardian ad litem “duties and requirements, not well defined,” increasing the likelihood “that future guardians ad litem be blindsided by duties not specific or implied in the trial judge’s appointment and subsequent orders,” and deterring attorneys from accepting appointments to be guardians ad litem.

Id. ¶ 27.

The Supreme Court Reviews the Case

Following the appellate court’s decision here, the guardian ad litem petitioned the Illinois Supreme Court to review the appellate court’s decision. The Illinois Supreme Court is not required to review every decision from a court of appeals (this Illinois Bar Journal article estimates that the Supreme Court grants 2 to 4% of the petitions filed).

In the Petition, the guardian ad litem argued that the Supreme Court should address the issue because the Appellate Court’s ruling conflicted with prior rulings of the First and Second Districts, as well as the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals and District Courts applying Illinois law. See Davidson v. Gurewitz, 2015 IL App (2d) 150171, ¶ 11, appeal denied, Davidson v. Gurewitz, 2016 Ill. LEXIS 195, 48 N.E.3d 672 (Jan. 20, 2016) (“[W]e hold that the common law affords defendant absolute immunity from suit related to his court-appointed duties as child representative.”); Vlastelica v. Brend, 2011 IL App (1st) 102587, ¶ 36, appeal denied, Vlastelica v. Brend, 2011 Ill. LEXIS 2102, 962 N.E.2d 490 (Nov. 30, 2011)) (same); Heisterkamp v. Pacheco, 2016 IL App (2d) 150229, ¶ 11, appeal denied, Heisterkamp v. Pacheco, 2016 Ill. LEXIS 1013, 60 N.E.3d 873 (Sept. 28, 2016) (finding court-appointed experts asked to advise on the best interests of a child are entitled to absolute immunity); Cooney v. Rossiter, 583 F.3d 967, 970 (7th Cir. 2009) (“Guardians ad litem . . . are absolutely immune from liability for damages when they act at the court’s discretion. They are arms of the court, much like special masters, and deserve protection from harassment by disappointed litigants just as judges do.”); Scheib v. Grant, 22 F.3d 149, 157 (7th Cir. 1994) (“We believe that the Illinois Supreme Court would find this reasoning persuasive and grant a court-appointed GAL absolute immunity from lawsuits arising out of statements or conduct intimately associated with the GAL’s judicial duties.”).

The guardian ad litem further argued that the Appellate Court’s decision disregarded the important public policies for providing absolute immunity to guardians ad litem acting within the scope of their duties, and if left undisturbed, would create a confusing and uncertain standard, imply unknown duties upon guardians ad litem, deter the acceptance of guardian ad litem appointments, and hinder the effective administration of justice in cases involving minors.

The Supreme Court granted the petition. After the parties submitted additional briefs (including a brief amicus curiae by the Illinois Trial Lawyers Association), the Supreme Court heard oral arguments on March 13, 2019.

The parties, along with the bench and bar, now await the Court’s decision.